“This Time, I’m Gone for Good”: Does the Labor Market Have Long COVID?

Last Friday, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell spoke at a Bank of International Settlements conference. He said, “I do think it’s time to taper, I don’t think it’s time to raise rates.”

On the rationale for tapering, he acknowledged that inflationary supply chain pressures are likely to persist longer than expected, but said that inflation pressures are likely to abate next year (commentary earlier this year was for the end of 2021 easing of “transitory” inflation).

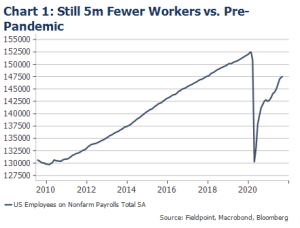

On the rationale for not raising rates, Powell pointed to the five million fewer workers in the labor force compared to pre-pandemic as the reason that the Fed should not be raising rates soon (Chart 1). He said, “We think we can be patient and allow the labor market to heal.”

But does the market believe him on either point?

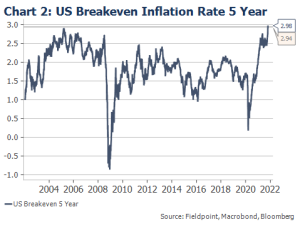

At the same time as Powell was trying again to break down signaling theory (we describe this in detail here), market-based inflation expectations were hitting a 20-year high (Chart 2) and the bond market was pricing in a greater probability of the fed funds rate increases.

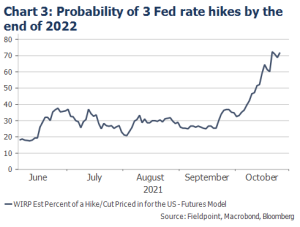

As implied by futures pricing, the probability of three rate hikes by the end of 2022 has surged to 70% (Chart 3).

To achieve this pace of rate hikes in 2022, the Fed would first need to finish tapering. This means the Fed would need to follow Governor Waller’s prescription of tapering “early and fast,” a policy path that is far more hawkish than any of Fed Chair Powell’s and the other doves’ commentary.

Powell typing rate hikes to the reentrance of the five million fewer workers employed today versus pre-pandemic, while the market is already pricing in higher rates.

So does this mean the market expects these workers to come back quickly in order to satisfy the Fed’s employment target OR does the market think this target will be abandoned, with other pressures leading the Fed to raise rates?

The former is possible, but not likely given the pace of hikes priced in.

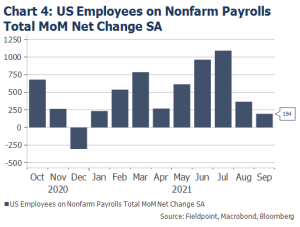

Chart 4 shows the monthly gains in non-farm payrolls in 2021. You can see the big one million+ hires in July, followed by the much smaller gains in August and September. These smaller gains have been explained away by factors like the Delta variant weighing on service jobs, dampening people’s desire to return work, and delaying the full reopening of in-person schools.

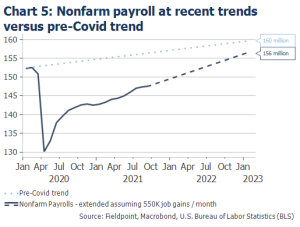

Some of these pressures are certainly starting to abate. So, let’s assume that job gains going forward will be close to the average of the last three months of 550k (consensus for October is for 385k, after having been beaten down by repeated large downside surprises). We can see in Chart 5 that at this rate, it would take well into 2023 to return to the pre-COVID trend of nonfarm payrolls (earlier to reach the January 2020 level).

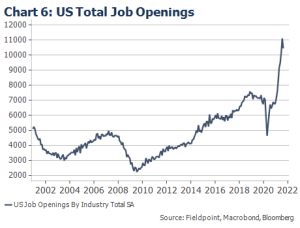

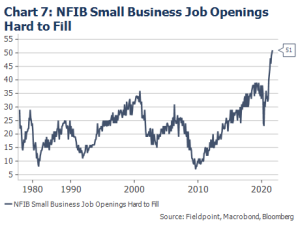

And note this is not for lack of jobs available. Job openings are at a record high (Chart 6), while businesses continue to report challenges filling jobs (Chart 7).

But can we assume that people will return to the labor market at this 550k pace? Or that the full five million people who remain out of the labor force today will ever return?

This is where the labor market is showing signs of “long COVID.”

Based on the impact of the prior pandemic, there is precedent to expect that the COVID experience over the last 20 months will have long-run impacts on our labor force.

First, we know that the pandemic has sparked accelerated retirements in the U.S., with estimates of two million more workers compared to the normal trend having retired since the pandemic began. Roaring markets have boosted the value of retirement investment accounts, putting retirement within reach for many, with an added nudge from higher savings built lockdown/stimulus and likely some health/safety concerns.

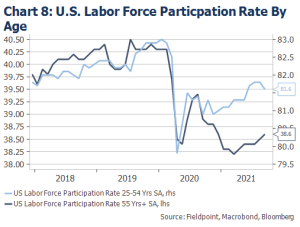

We can see this impact by looking at labor force participation rates by age cohort. The younger 25-54 age cohort has seen a more robust recovery in labor force participation, while the 55+ cohort remains depressed (Chart 8).

Second, there is a similar story to tell my gender. Both women’s and men’s labor force participation rates are below pre-pandemic levels, but men’s participation rate is closer to pre-pandemic levels than women’s (Men is 1.6% lower than pre-pandemic, Women is 1.9% lower than pre-pandemic, representing thousands of workers difference). Some, like Nicholas Christakis, argue that women, who tend to assume the responsibility of caregivers, will lose decades of labor force participation rate growth.

Third, we know there are some amount of workers who have started their own business and are unlikely to return to “traditional” employment. They are counted in the employment numbers, have the ability to hire others as well, but are not available to work jobs that they might have previously held. This helps to explain the elevated level of job openings and quits.

So when we put this all together, we can see that the five million workers available to return to the labor force could be far lower in reality. This would indicate that the labor market is tighter than the Fed is currently acknowledging. This could spell for continued wage gains which would feed into continued elevated inflation readings and higher inflation expectations.

Of course, there is a layer of it being too soon to make confident projections about how quickly people will return to the labor force. The supplemental unemployment benefits only ended in September, which had some impact on keeping people out of the labor, while school reopening delays and COVID fears are still present.

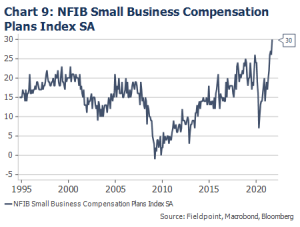

We also know that employers are having to raise wages to find the workers they need, as shown by Chart 9 with the NFIB Small Business Compensation Plans Index at a record high. As wages continue to be pushed higher, partially thanks to competition with other employers, it is likely that some workers will be drawn back into the labor force.

But even with these, it appears that there will be growing pressure on the Fed to change its messaging around labor, acknowledging the tight labor market in some areas and the structural changes in the labor market that have resulted due to COVID. This, along with continued elevated inflation readings, could mean stepped-up hawkish commentary out of the Fed, which could likely pressure equity P/E multiples further and spur greater equity volatility (as we discuss in detail here).

Disclosures

Important Legal Information

This material is for informational purposes only and is not intended to be an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any security or to employ a specific investment strategy. It is intended solely for the information of those to whom it is distributed by Fieldpoint Private. No part of this material may be reproduced or retransmitted in any manner without prior written permission of Fieldpoint Private. Fieldpoint Private does not represent, warrant or guarantee that this material is accurate, complete or suitable for any purpose and it should not be used as the sole basis for investment decisions. The information used in preparing these materials may have been obtained from public sources. Fieldpoint Private assumes no responsibility for independent verification of such information and has relied on such information being complete and accurate in all material respects. Fieldpoint Private assumes no obligation to update or otherwise revise these materials. This material does not contain all of the information that a prospective investor may wish to consider and is not to be relied upon or used in substitution for the exercise of independent judgment. To the extent such information includes estimates and forecasts of future financial performance it may have been obtained from public or third-party sources. We have assumed that such estimates and forecasts have been reasonably prepared on bases reflecting the best currently available estimates and judgments of such sources or represent reasonable estimates. Any pricing or valuation of securities or other assets contained in this material is as of the date provided, as prices fluctuate on a daily basis. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Fieldpoint Private does not provide legal or tax advice. Nothing contained herein should be construed as tax, accounting or legal advice. Prior to investing you should consult your accounting, tax, and legal advisors to understand the implications of such an investment.

Fieldpoint Private Securities, LLC is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Fieldpoint Private Bank & Trust (the “Bank”). Wealth management, securities brokerage and investment advisory services offered by Fieldpoint Private Securities, LLC and/or any non-deposit investment products that ultimately may be acquired as a result of the Bank’s investment advisory services:

![]()

Such services are not deposits or other obligations of the Bank:

– Are not insured or guaranteed by the FDIC, any agency of the US or the Bank

– Are not a condition to the provision or term of any banking service or activity

– May be purchased from any agent or company and the member’s choice will not affect current or future credit decisions, and

– Involve investment risk, including possible loss of principal or loss of value.

© 2021 Fieldpoint Private

Banking Services: Fieldpoint Private Bank & Trust. Member FDIC.

Registered Investment Advisor: Fieldpoint Private Securities, LLC is an SEC Registered Investment Advisor and Broker Dealer. Member FINRA, MSRB and SIPC.